William McKinley (1843-1901) was the 25th president of the United States. During his administration, the two important issues of tariff and currency were overshadowed by the Spanish-American War of 1898. Under his administration, the United States gained its first overseas possessions, presenting the country with new problems of world power and territorial expansion.

BIOGRAPHY:

William

McKinley was born in Niles, Ohio, on January 29, 1843, the seventh child

of William and Nancy McKinley. William briefly attended Allegheny

College, and was teaching in a country school when the Civil War broke

out. Following the war, he studied law, began practicing in Canton

Ohio, and married Ida Saxton.

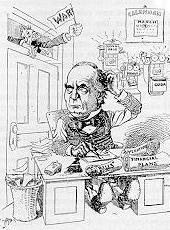

At age 34, McKinley won a seat in Congress. He was appointed to the Ways and Means Committee. Those who served with him attest that in his votes, he often sided with the public and avoided private interests. During his 14-year tenure with the House, McKinley became a leading expert on tariffs. He later became governor of Ohio, serving two terms. As a congressman, governor and later, president, McKinley, a man of moderation and compromise, held firmly to two beliefs: favorable tariff to stimulate American business and limited coinage of silver.

William McKinley was nominated as the Republican candidate for president with the assistance of Mark Hanna, a wealthy industrialist. Favoring tariffs as protection for prosperity for the nation and a limit on silver, he defeated William Jennings Bryan, whom many feared as a threat to the government in the election of 1892.

As president, McKinley was converted to the idea of international bimetallism—an agreement of several countries to use both gold and silver as the basis for their currency. He later favored maintaining currency by using the gold standard, opening the way to passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1900.

As a member of Congress in 1888, his views for protective tariff were

unequivocal:

“Let England take care of herself. Let France look after her own interests. Let France look after her own interests. Let Germany take care of her own people; but in God’s name let America look after America.”In 1890, he sponsored a protective tariff that bears his name; the highest tariff in the nation’s history. During his tenure as governor of Ohio and later as president, McKinley favored mediation between capital and labor; often favoring the poor.

Following the Spanish-American War and his re-election in 1900,

McKinley unveiled a new, broader way for an internationally minded

America. Ironically, this was to become his last speech for on the

following day, September 6, 1901, he was mortally wounded from an

assassin’s bullet:

“The period of exclusiveness is past. The expansion of our trade and commerce is the pressing problem. Commercial wars are unprofitable. A policy of good will and friendly trade relations will prevent reprisals. Reciprocity treaties are in harmony with the spirit of the times, measure of retaliation are not. If perchance some of our tariffs are no longer needed, for revenue or to encourage and protect our industries at home, why should they not be employed to extend and promote our markets abroad?”

McKinley

skillfully manipulated both the public and politicians. Yet, his

domestic program and achievements were overwhelmed by foreign policy,

which came to dominate his administration. Ever a proponent for a

healthy economy, he supported creating new foreign markets for United

States products. Foreign markets, however, put America at risk to

become entangled with the affairs of other nations. For instance,

Americans became embroiled in the Cuban revolution of 1895 against Spain

Americans for many reasons: American sugar companies lost trade and profit

due to the fighting; some saw a declaration of war against Spain as

necessary for growth of American trade while others claimed that Spanish

tyranny had to be stopped in the Western Hemisphere. Lastly, there was a

strong desire for overseas coaling bases for ships in the U.S.'s new steel

navy.

McKinley

skillfully manipulated both the public and politicians. Yet, his

domestic program and achievements were overwhelmed by foreign policy,

which came to dominate his administration. Ever a proponent for a

healthy economy, he supported creating new foreign markets for United

States products. Foreign markets, however, put America at risk to

become entangled with the affairs of other nations. For instance,

Americans became embroiled in the Cuban revolution of 1895 against Spain

Americans for many reasons: American sugar companies lost trade and profit

due to the fighting; some saw a declaration of war against Spain as

necessary for growth of American trade while others claimed that Spanish

tyranny had to be stopped in the Western Hemisphere. Lastly, there was a

strong desire for overseas coaling bases for ships in the U.S.'s new steel

navy.

McKinley preferred an autonomous Cuba but public indignation of

claimed Spanish savagery brought pressure upon the President for war.

Unable to hold back the Congress or the American people, McKinley

delivered his message of neutral intervention in April 1898.

Congress voted three resolutions tantamount to a declaration of war for

the liberation and independence of Cuba. In a message to Stewart

L. Woodford, the United States ambassador to Spain, dated March 26,

1898, the State Department expressed the American position regarding

Cuba in its Ultimatum to Spain:

“The President has evidenced in every way his desire to preserveIn spite of a conditional revocation of the reconcentration policy and plans for partial Cuban autonomy, War was declared on April 25, 1898, ignited by Spain’s refusal to grant independence to Cuba, popular pressure and the destruction of the U.S. battleship Maine. The Spanish-American War was brief, and at its end in August 1898, the United States emerged as a world power. McKinley had played a large role in coordinating the military effort, functioning directly as a Commander-in-Chief. Peace negotiations with Spain resulted in United States occupation of Cuba until it became independent in 1902, and the acquisition of Puerto Rico and Guam. Unwilling to let the former Spanish possession, the Philippines, fall into a competing hands, McKinley directed his emissaries to acquire the islands. After receiving news of the victory of Admiral George Dewey over the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, McKinley managed a campaign to convince the American people that the islands must become the possession of the United States. Despite the opposition of anti-imperialists, McKinley engineered senate ratification of the Treaty of Paris, an accomplishment that broadened the powers and influence of the president.

and continue friendly relations with Spain. He has kept every

international obligation with fidelity and wants honorable peace.

He has repeatedly urged the government of Spain to secure such

a peace. Peace is the desired end. For your own guidance, the

President suggests that if Spain will revoke the reconcentration

order and maintain the people until they can support themselves

and offer to the Cubans full self-government, with reasonable

indemnity, the President will gladly assist in its consummation.”

McKinley (left) and General Wheeler (right) inspect a

military hospital on Montauk Point

McKinley reflected the sentiments of various groups favoring war as stated in his War Message:

“The present revolution is but the successor of other similar insurrections which have occurred in Cuba against the dominion of Spain, extending over a period of nearly half a century, each of which, during its progress, has subjected the United States to great effort and expense in enforcing its neutrality laws, caused enormous losses to American trade and commerce, caused irritation, annoyance, and disturbance among our citizens, and by the exercise of cruel, barbarous and uncivilized practices or warfare, shocked the sensibilities and offended the humane sympathies of our people.”The consequences of the Spanish-American War shaped the rest of McKinley’s presidency. In the Philippines, the army dealt with a native riot in a prolonged and nasty guerilla war while William Taft was setting up a civil government with guidance from American administrators.

The overshadowing of the Spanish American War by the American Civil

War (1861-1865) and U.S. involvement in World War One (1917-1918),

combined with a more recent national feeling of guilt about the

Spanish-American War have clouded McKinley’s reputation. The charisma of

his successor, Roosevelt, has further obscured

McKinley’s achievements. McKinley, it should be noted strengthened

the presidency, traveled widely, and gave the press greater access to

the White House. His management of Congress was masterful. The

evolution of the bold modern presidency began during his term in

office. McKinley laid the basis for further growth of the office

under Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Benton, William, The Annals of America. ( Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.,Vol. XII, 1968).

---- "McKinley’s War Message." (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1968).

Glad, Paul W., "McKinley, Bryan and the People," Grolier Electronic Publishing, Inc., (1964; reprinted 1991), CD-ROM.

Grolier Electronic Publishing, Inc. "William McKinley," 1995, CD-ROM.

Morgan, H. Wayne. "McKinley and His America," Grolier Electronic Publishing, Inc., (1963), CD-ROM.

Sievers, Harry J., William McKinley 1843-1901. (New York: Oceana Publications, Inc., 1970).

“William McKinley”, January 1997, Snap.com, (Online).