The word "torpedo" should be applied only to the "locomotive torpedo" (a relatively new weapon in the Spanish American War period) and not to submarine mines that have a static character. This confusion is perfectly reflected in the orders received by Admiral Montojo giving him instructions to defend Philippine ports with torpedoes. Admiral Montojo did not have torpedoes, and, more importantly, torpedoes were not, and are not, normally used to attack ships from land. Therefore the message from Madrid, without any doubt, was referring to mines. It is important to take into account the differences between both concepts, as they are defined below, between mines and torpedoes used during the Spanish-American War:

A torpedo was a metallic projectile, cylindrical-shaped, filled with an explosive and with a contact mechanism that induced the explosion. Torpedoes were thrown by means of tubes on board the warships and, once in the sea, they were driven by a compressed-air propeller.

Submarine mines were divided into two varieties: torpedoes arranged to be discharged on a circuit connected with the shore, (shore circuit torpedo or controlled mines), and self-acting torpedoes, (contact mines), exploded by electrical, chemical, or mechanical means exclusively through contact. Most of the Spanish mines, used to defend ports and harbors, were of the submarine type.

SUBMARINE MINES:

A submarine mine was filled with an explosive and had a metallic box filled with nitrocotton, dynamite or nitro-glycerine which exploded either when a vessel collided with it, (contact mines) or when it was activated by means of an electric cable linking the mine with the coast. On land the cables were connected to a Breguet-type detonator. The detonator produced electricity that detonated the nitrocotton and, consequently, the explosive of the mine.

The contact mine was only used to protect areas of secondary

importance. Its operation was "blind and unintelligent" since it could

destroy both friendly and hostile ships. The explosion could not be

controlled from shore and, once anchored, the mine was a risk to any

vessel crossing over it until the mine was removed or exploded. The

danger during removal was so great that the mine would have to be

destroyed rather than removed. The advantage of this type of mine was

that it could be rapidly laid, without complex instruments and shore

attachment and it did not require expert electrical skill in

installation and operation, as did the mines discharged on a shore

circuit.

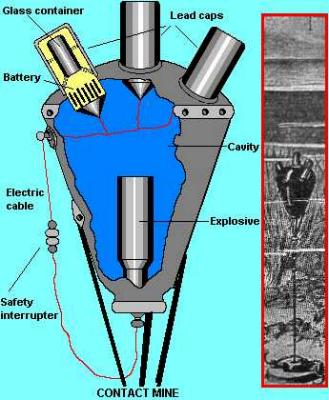

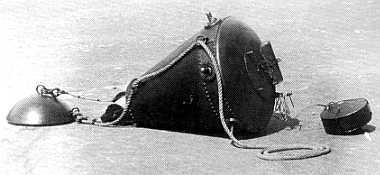

Contact mines consisted of an iron hollow container that facilitated

their flotation and contained the explosive load. In order to keep a

suitable depth, these mines were anchored. The most often used method

for inducing the explosion of a contact mine was based on a system of

lead caps that contained a glass container filled with an acid liquid.

When a ship collided with any of these caps, they were crushed and,

because of the rupture of the glass, the acid was introduced into a

zinc-coal battery located under the lead cap. This generated an electric

current that, when transported by a leading wire to the explosive,

induced the incandescence of a platinum resistor wire and the subsequent

explosion.

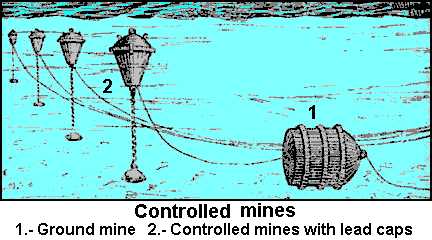

Controlled mines, (shore circuit torpedoes) were divided into two classes: buoyant and ground mines. The shape of a controlled mine was conical, spherical or cylindrical, constructed of two metallic parts riveted together. The metal was pressed out thin from low - carbon steel, securing the utmost tensile strengths.

The ground mine was attached to the sea bed by its own weight. The buoyant mine was used in deeper waters, (more than thirteen meters). In shallower waters, however, the ground mine became more suitable. The buoyant mine was anchored to the sea bed. Its circuit-closing apparatus was in the very heart of the mine itself, and so constructed that a slight shock to the mine case discharged it.

Controlled mines exploded manually. They were linked to the ground observation post by means of an electric cable that was used to close the circuit when the enemy ship was over the mine. The observer had to know the situation of the enemy ship and, for that purpose, he made use of telemeters, reflection in "camera obscura", or other similar device. Some types of controlled mines had also lead caps and they could operate also as contact mines; however, this design was not very frequent.

Both, contact and controlled mines had a disadvantage. They had a

tendency to drag, (they did not remain indefinitely in the same position

because their anchorage was not perfect and the longshore currents

modified their location).

SOME HISTORICAL FLASHES:

Towards the end of 1883 the Spanish Government initiated negotiations

with Pietruski, an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, who proposed to

sell the patent of a submarine contact mine invented by him to Spain

with a price of 200,000 pesetas, (about $1,625 US today). One year

later, the Spanish commodore Joaquin Bustamante presented a domestically

developed and lower cost design for a contact mine that could be used to

defend the Spanish ports that did not have suitable submarine defences.

Consequently the Spanish Armada cancelled the negotiations with Petruski

and gave a subsidy of 10,000 pesetas, (about $63 US today), to

Bustamente in order to support his project.

After obtaining this subsidy and receiving official support and loans Bustamante carried out tests of his prototype mine with satisfactory results and, by Royal Order of May 9, 1885, Bustamante's mine was declared standard issue mine. The production of 100 units was started immediately. Between 1884 and 1886 the submarine defence of the Spanish ports was based on Bustamante's mine, (ground, buoyant and contact mines).

The use of mines by Spain during the Spanish-American War could have had a paramount role in the development of military operations. However, because of the bad quality and maintenance of the existing mines, they were totally useless during the war. In addition, Bustamante´s newest mine could not be sent to Cuban and Philippine ports because Admiral Cervera had been informed that all Puerto Rican and Cuban ports had been adequately mined.

An example of this disastrous situation is the fact that all the submarine mines failed, even when their cables were caught by the propellers of USS MARBLEHEAD and USS TEXAS!

In the Philippines, Rear-Admiral Montojo had neither many nor good mines. There were 14 British mines, (Mathieson system), but without some components, such as electric cable and whose fuzes were being installed at the Arsenal in Cavite. These mines should have to be used to close Subic Bay but some of their components were in a bad condition, including the nitrocotton.

Other twenty two mines were improvised by filling "normal" buoys with explosives and installing torpedo detonators in them. These malformed creatures were placed in Boca Grande, at the entrance of Manila Bay, and they could be very efficient, but they were few to close effectively said entrance and, in addition, the strong submarine currents displaced these mines from their position. At the last moment other few controlled mines were installed in front of the Arsenal in Cavite.

Another example of those calamitous mines took place at the beginning of the Battle of Manila Bay. Because the explosion of two mines ahead the USS OLYMPIA has been described, it seems to be very clear that Admiral Montojo had controlled mines. Possibly these two mines were operated from the coast and had dragged from their planned locations or the Spanish defenders did not have a suitable observation post or the visibility was not good enough as to use the mines adequately. In any case, the probability of destroying the OLYMPIA with that kind of material was lower than the probability of destroying her with a pie!

Mine scarcity was a serious problem for Montojo. He asked Madrid for new units but by that time, it was already too late. When the war started, the mines coming from Spain were in Singapore where the British prohibited their delivery to Manila. Because of this, the Spanish armed forces in the Philippines had to rely on poorer solutions, such as reinstalling faulty existing mines. For this purpose, Montojo requested the delivery of nitro-glycerine from Spanish consulate in Hong-Kong, but Montojo received only several kilometres of electric cable.

Howser, Doug (image of contact mine horn)

Iriarte, L. 1898 - La Guerra Hispano Americana en Puerto Rico. http://home.coqui.net/sarrasin/index.htm

Liaño Huidobro, A. (Commander; Spanish Navy).Personal communiqué. 1999.

Rodríguez González, A. R.. La Guerra del 98. Agualarga Editores. Madrid. 1988.

Rodríguez González, A. R.. Operaciones de la Guerra de 1898 - Una revisión crítica. Editorial Actas. San Sebastián de los Reyes. 1998.